The Way to Campaign in a COVID-19 World.

The Way to Campaign, Period.

This is a country of 330 million souls living on 3.5 million square miles of land, some of which is separated by even greater amounts of water, or Canada. A presidential candidate can’t help but wish that he could take his {sigh} message to every American, everywhere. But there is just too much ground to cover. Even for congressional candidates, their districts are pretty big, averaging about 750,000 constituents and spanning as many as 570,000 square miles. Senate districts range from 600,000 to 40 million people and cover up to 650,000 square miles. The primary messengers of campaigns are the candidates, to be sure, but to get their messages out to everyone they are trying to reach, they are going to need a little help.

Surrogates

There was a time when it was TV ads that helped candidates reach voters everywhere. But everywhere just isn’t what it used to be. TV ads are expensive, and not that many people under 40 are watching them. To cover all that ground, whether virtual or hard pavement, you have got to use surrogates: fellow politicians, former presidents (thank you President Obama), community activists, religious leaders, entertainers, athletes, union members, YouTubers, and social media icons. Get them out there, representing the campaign at events, doing interviews with journalists and talking heads, posting to social media, wear campaign t-shirts, and so on. Supportive political and nonprofit organizations, each with their own networks capable of mobilizing and spreading the word, should be enlisted as well. And don’t forget to ask your surrogates to invite their friends to help out, too. Which brings me to the modern campaign’s most important messenger: the supporter.

Supporters

Thousands, even millions of campaign advocates, supporting the candidate online, generating their own content (called user-generated content) are, en masse, a powerful weapon. Especially when the relational organizing approach is employed via social media posts and P2P communications—put simply, supporters mobilize their friends and networks through social media, some of those friends become volunteers themselves, and they, in turn, reach out to their networks. The campaign’s supporters, armed with little more than their social media accounts, P2P apps, and the candidate’s website, are producing original content that promotes the candidate’s message. In the old days, having so many spokespeople for a campaign was more hindrance than help and caused leadership to fret that their carefully crafted messages would spiral out of control. Today, campaign communications teams can fearlessly loosen their grips, partly because of the decentralized nature of social media communications, partly because campaign resources are so readily accessible to every volunteer, and partly because personalized messages engender trust. Together with surrogates and partner organizations, these volunteers form quite an army. This is how it works now.

Army

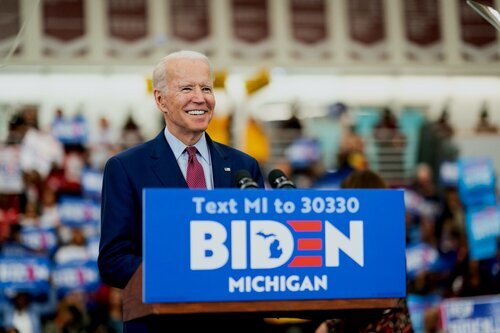

Welcoming and inviting user-generated content makes possible communicating with thousands, even millions of potential voters, and specifically, voters the campaign otherwise may not have reached. After all, 72% of adults use at least one social media site (about 90% of Gen Y and Z and 40% of the 65+ crowd). If I post a message about Joe Biden’s strength & kindness and 10 of my 1,000 Facebook Friends share it, and 5 of each of their 500 Facebook Friends share it, and 5 of each of their 500 Facebook Friends share it, that’s 28,500 + a lot of people who may see it, all from one post that cost somewhere between nothing and next-to-nothing. This doesn’t mean that going digital is going to cost nothing, it just means that there is a lot you can do on a limited budget and a tremendous amount you can do with a sizable budget.

Posting on social media websites is only one way for supporters to share messages. P2P (peer-to-peer) communications refers to direct messages between individuals, such as texting, DMs, and chat groups. Volunteers can text and chat using platforms like Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram DMs, GroupMe, Hustle, GetThru, CallHub, and Team (by Tuesday). Through P2P communications, supporters convey the campaign message in their own way directly to their friends, family, and social media acquaintances. In addition, with permission, campaigns can also run a supporter’s social media contacts against voter files or target lists to home in on high-priority voters who might need some persuading or who might be good fundraisers.

These campaign soldiers are critical to a campaign’s success. Their weapons are their messages, discharged via social media posts, texts, DMs, and chat groups. And, as with relational organizing, they participate because they believe in the candidate and the cause. None of them has incredibly large followings, but there are many of them.

Special Forces

Some Democrats have also been building a sort of special forces command within this army. These social-media-elite are comprised of influencers and micro-influencers. Influencers are those who have sizable followings on line, from 10,000 to millions. They might be politicians, entertainers, sports stars, religious leaders, well-known journalists, or other public figures. Micro-influencers are not as famous, but within their own field, passion, or niche they are known and well regarded. They will typically have between 1,000 and 10,000 followers. The idea here and with the broader supporter army, is that people tend to believe what they hear when it comes from a trusted source, like a friend or a respected leader, so it is wise for campaigns to tap trustworthy messengers who have large followings. Influencers and micro-influencers are trusted sources for their followers, and because they have so many followers, that is valuable to campaigns. If campaigns ask these influential supporters to craft their own messages, putting their own personal touch on broad campaign themes, it will ring authentic because it is. That is persuasive and far-reaching.

Whether a campaign has special forces or just foot soldiers, another reason user-generated content works so well is that people really like to create and share videos and graphics and cartoons and art and photos and gifs and memes and quips and Tweets and jokes. Presidential campaigns like those of Pete Buttigieg, Andrew Yang, Bernie Sanders, and, unfortunately, President Trump have demonstrated that these tactics give long-shot candidates a way to gain name recognition, create buzz, build support, and sometimes win a lot of votes. Like fans of Fabergé Organics Shampoo with Pure Wheatgerm Oil and Honey, “You’ll tell two friends, and they’ll tell two friends, and so on and so on and so on."

Cancel Culture in Politics

I want to say something about canceling, and bear with me, I do have a point here. Canceling is the dark side of going viral (apologies for the expression). It is the social media rumor mill where the accusation becomes the proof. Canceling is when a social media personality or otherwise famous person is ostracized in reaction to something they have said, done, written, or shared. I learned about this when I stumbled on Natalie Wynn and her ContraPoints YouTube tutorial on the subject. This is how it works.

Let’s assume that a fashion or entertainment or sports icon publicly accuses another icon of having done something offensive. The accusation is not so severe that it would ruin a person, but it could be taken the wrong way. The accusation is picked up by social media, but instead of simply repeating what’s been alleged (“I heard that he tried to get her to stay”), the social media grinder spins and pulverizes the original accusation into something much worse in an ugly game of telephone. First, an unfavorable Presumption is made about the accused and the original accusation is hardened (from “I heard that he tried to get her to stay” to “he made her stay”). Next, the Presumption of Guilt statement is transformed into one in which the specifics are obscured or erased and replaced by a generalized statement via Abstraction (from “he made her stay” to “he is aggressive and a misogynist”). This is harsh and leaves readers to imagine the worst about the underlying actions because the statement is vague. Then the attacks morph into a specific accusation (from “he is aggressive and a misogynist” to “he is a rapist”). Notice how the attacks no longer focus on behavior and instead focus on character—I call this the Ad Hominem step, Wynn uses the more sophisticated term Essentialism and explains that the personalities most vulnerable to this are those who are easy to envy, easy to resent, hard to relate to, and hard to sympathize with. The pillars of this kind of essentialism are relevant to the political climate of 2020 and, so far, good news for Joe Biden.

At this point, the original accusation has been escalated to something worse and further material is unearthed for fodder (the accused is caught on tape lamenting the fact that another woman didn’t invite him in after a long and expensive date). And in a defensive posture, the haters express faux outrage in the Pseudo-Moralism/Intellectualism phase, using morality as a pretext for their actual spite, envy, revenge, rage, projection, or tribalism. Let’s assume that the aggrieved party makes a half-way decent apology for the latter statement (”I am truly sorry. It was insensitive of me to discuss my date publicly and to describe my disappointment as my date’s character flaw.”). In the No Forgiveness stage, the social media world ignores the apology or finds it lacking and further escalates the attacks. Finally, we come to the Transitive Property of Cancellation in which a friend of the accused is skewered for sharing a totally unrelated Instagram Story the accused has posted, immediately being branded a fellow misogynist and a possible gang raper thanks to the high school principle of guilt by association. Progression through all of these steps is accomplished within a few days, but the attacks can last for weeks. And that is cancel culture, the escalation of mild conflict that ultimately results in the loss of millions of followers and a good deal of personal anguish. Neither understanding nor adherence to facts plays a role.

So, why the long exposition about cancel culture? I believe that this is an excellent way to understand the power of social media in politics. These tactics are well understood by the Trump campaign. And, while Democrats have taken to spinning like never before as Republicans dig themselves deeper and deeper into the Trump pit of despair, losing credibility with each ridiculous statement and hideous act, spinning is not the same as canceling. With canceling, social media weaponizes the lesser stories of opposition research, more than any one microphone ever could. A toxic conversation moves quickly from social media to cable to print to broadcast news. It may even result in the the loss of an election and the “canceling” of a politician’s career. Everyday people who are otherwise not engaged in the political process are encouraged or feel otherwise possessed to make outrageous statements about the candidates’ opponents. Sometimes, the accusations are true. Sometimes, they are not. The most potent contain grains of truth that float in a cup of lies until they dissolve and corrupt the whole damn thing. The damage can be politically fatal. I advise all Democratic campaigns to sharpen their digital skills, make use of their digital armies, run offense with positive messages about how their candidates will bring light to the darkness, and heed the ugly nature of social media discourse. 2020 is no year for ostriches—after all, it is the year of the rat.

In recent weeks, it has been made public that the Biden campaign is consulting with former primary candidates like Buttigieg, O’Rourke, Harris, Warren, Klobuchar, Yang, Sanders, and Booker. In addition, they’ve brought on a few staffers from one or two of the campaigns. This is good. Very good. What I would like to see is the Biden campaign brining on board senior staff from the Buttigieg campaign and hiring the best digital gurus from political and digital firms, some to serve as consultants, some as staff. There is much to do and much to be ready for. By deploying smart technology and making use of what social media platforms have to offer, we can win this thing. I do not suggest that Joe Biden should employ the underhanded tactics of President Trump, not at all. I simply mean that he must put folks around him who understand how it all works, understand how Trump’s digital strategy and tactics helped him win in 2016, and understand how a Biden campaign can achieve the same results without being underhanded. Winning is the only option.